This is my second of three entries into The Film Vituperatem's Hitchcock Blog-A-Thon. Part 3 comes on November 15, when the actual event takes place.

There is one accusation that has been directed at

Alfred Hitchcock more than any other; that he is a misogynist. Women in his films are disciplined, and these punishments range from minor embarrassment to death. However, the woman is always castigated for committing some sin within the Hitchcock universe. Often, the sin is trying to be someone the woman is not. This is best exemplified in

Rebecca. The heroine, who has no name throughout the film, tries to be like Rebecca by being authoritative and attractive. However, she is neither naturally beautiful nor powerful, and so she is punished.

In

Rebecca, the main character desperately tries to be dominant like Rebecca, but suffers in each attempt. The primary visual motif used is to show a character’s power is their placement within the frame. The heroine spends a great deal of time on the right side of the screen. This is used to show her relative weakness. Other characters, like her husband, Maxim deWinter, are more powerful and are shown on the left side of the screen. On the compass rose, the left side is west, and Rebecca lived in the west wing of Manderley. Hitchcock uses this to associate the left side of the screen with the power Rebecca holds over the film. It was Rebecca who determined how Manderley was run and she who decided how she and her husband, Maxim got along. Whenever the heroine appears on the left side of the film, she is in some way punished, usually verbally. As she grows bolder and attempts to exert more power, her castigations grow stronger until she nearly kills herself.

The protagonist begins the film in Monte Carlo as the assistant to Mrs. Van Hopper, and as such she is constantly in a position of subservience. This is shown visuall

y by the heroine’s constant position at the right side of the film. She always stands to the right of other more forceful characters, such as Mrs. Van Hopper and Maxim. There is only one scene in Monte Carlo in which the main character appears to the left o

f another character. This occurs after Maxim proposes to the protagonist. Immediately following his proposal, we see a conversation with her on the left. Hitchcock shows her usurping Rebecca’s spot of power, but it doesn’t take long for Mrs. Van Hopper to put her in her place with verbal abuse. Though she is rebuked for taking this position of power over her former boss, the effect is minimal. She feels a little shame, but she is too excited by the prospect of being married to Maxim for this to affect her in any meaningful way. Nevertheless, she then returns to the right of the screen, as powerless as before.

After Mrs. Van Hopper leaves, our heroine becomes the second Mrs. deWinter and she appears to the left of the screen much more often. There is even an extended scene in which she appears to the left of Maxim, something that never happened in Monte Carlo. This occurs when she discovers Rebecca’s boathouse. She disobeys Maxim when he asks her not to go down to it, and for this she is bestowed the position of power on the left side of the screen. However, this bit of self-determination incites Maxim to intensely yell at her. This is the worst sort of punishment for her to endure, because it is being delivered by the man she loves so much. The glares and sly grins of Mrs. Danvers have much less effect on her.

While at Manderley

, the second Mrs. deWinter is constantly shown to the left of the servants. Being the mistress of Manderley, she holds authority, even over Mrs. Danvers. Because she holds the power of position that Rebecca once had, Mrs. Danvers repeatedly attempts to show the second Mrs. deWinter that she is inadequate, essentially punishing her for trying to be like Rebecca. Mrs. Danvers is forced to serve under the second mistress of Manderley, and so she exacts her revenge by putting the protagonist into two very difficult positions.

The first is when the protagonist enters the west wing. Here, Mrs. Danvers gives the second Mrs. deWinter a tour, and she appears to the

left of the protagonist for the first time in the film. Mrs. Danvers has full powe

r at this time, and so it is she who can be in Rebecca’s place. She shows the heroine all of the decadent items of clothing that Rebecca owned, forcing her to feel just how soft Rebecca’s furs and dresses are. After this, Mrs. Danvers shows the second mistress of Manderley where Rebecca slept and what nightgown she wore. This ultimately forces the second Mrs. deWinter to flee the west wing and change positions with Mrs. Danvers, enforcing her power even more. In response to this, Mrs. Danvers presents her second plan, one which almost causes the heroine to kill herself.

Mrs. Danvers’ plan and the motif of position within the frame reach their greatest intensity when the protagonist prepares her gown for a costume ball at Manderley. The second Mrs. deWinter has dressed up in the same gown that Rebecca wore the year before. She has deliberately kept her costume a secret from Maxim, so that she can surprise him. She descends the stairs as happy as she is ever shown in the film. However, when Maxim sees what she is wearing, he rebukes her for her choice. The heroine then almost kills herself from the embarrassment.

Most of this scene is presented in a shot-reverse shot format. The first shot is the protagonist’s perspective of the people at the ball; the second focuses intently on her face, showing nothing but the heroine in her full glory. It is not until she reaches the bottom of the stairs that she is shown in a shot with any other characters. At this time, she enters the screen from the left. She begins the shot outside of the frame, emulating Rebecca’s position. Rebecca spends the entire film off screen, too powerful to even exist on the same level of existence as the characters in the film. This effect is duplicated before the second mistress of Manderley enters the frame. As she enters, however, she is surprised to see Maxim outraged at her gown. Maxim’s anger and chastisement torture her thoughts until she can think of nothing but suicide. She has been punished for most egregious attempt to be like Rebecca with the strongest type of discipline she receives in the film.

The second Mrs. deWinter is also chastised for attempting to be beautiful. Beauty is a quality that only Rebecca can hold in the film, and most people only remember her for her beauty. Mrs. Van Hopper’s thoughts on Rebecca are limited to, “before she was married, she was the beautiful Rebecca Hildreth, you know.” Outside of this comment, Mrs. Van Hopper only mentions Rebecca’s death and the effect it had on Maxim. Similarly, Frank Crawley i

s given limited dialogue about his former mistress. Other than her death, he can only declare, “she was the most beautiful creature I ever saw.” By instilling these ideas about Rebecca into the second Mrs. deWinter’s head, the people surrounding the protagonist inevitably make her wish to be beautiful like Rebecca.

Nevertheless, it is in her attempts to be attractive that the second mistress of Manderley is punished. The first case occurs when Beatrice and the heroine are speaking after first meeting. Upon Beatrice’s suggestion, Maxim’s second wife pulls her hair behind her ears. When she does this, Beatrice can only exclaim, “oh no, that’s worse.” Since this is the protagonist’s first attempt to be beautiful, and it is easily reversible, she is only slightly chastised. She is berated more when she tries to imitate the style she saw in a beauty magazine. This time, it is Maxim who angrily snaps at her for her outfit, increasing the pain she feels. But nothing can compare to her ultimate attempt to be beautiful.

Every time she tries to make herself more beautiful, the second Mrs. deWinter is indirectly attempting

to make herself more like Rebecca. By Mrs. Danvers’ plan, the protagonist actually dresses in the same costume as Rebecca. This becomes the heroine’s most direct attempt to be like Rebecca, even though she only wanted to be beautiful. The fact that she is wearing this for a costume ball also serves the symbolic purpose of showing that beauty is merely a costume for the second mistress of Manderley. She is not attractive, so she can only pretend to be beautiful by wearing costumes. As the costumes grow more elaborate, she is castigated more severely until she almost commits suicide. This is her strongest punishment, yet she is saved from a terrible fate by Rebecca, the same presence who drove her there.

Rebecca tells the story of a woman who is disciplined for trying to be something she is not. She is not a naturally powerful person, and yet she presents herself as an authority in Manderley. Hitchcock shows this through her place on the screen and punishes her for it. Deception is the second Mrs. deWinter’s sin, and she must pay for it. In Hitchcock’s universe, no sin goes unpunished, and Rebecca shows this perfectly.

"Do you think the dead come back and watch the living?" - Mrs. Danvers, Rebecca

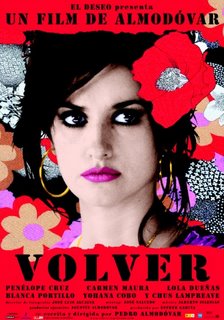

"Do you think the dead come back and watch the living?" - Mrs. Danvers, Rebecca er. It turns out that Augustina's mother and Raimunda's father were the ones having the affair. And then there's the final revelation which explains why Raimunda has been angry with her mother for so long.

er. It turns out that Augustina's mother and Raimunda's father were the ones having the affair. And then there's the final revelation which explains why Raimunda has been angry with her mother for so long.